Advancing Tradition

Stephen Rea, Féile na Laoch and the Grand Canyon.

I sat down in front of a man this Summer that organised a festival I was invited to and much to his chagrin, I apologised for failing in the role I was invited to fulfil.

I live what I consider to be a very blessed life. I am not a wealthy man, and I wouldn’t even consider myself to be a happy person. People light me up and so that may not be clear to an outside observer, but I idle in the depths, and happiness is only a small slice of life where meaning is constantly measured.

I feel blessed because I have a beautiful family, a strong raison d’etre and I have the curious good fortune of finding myself in the company of people I genuinely admire, sometimes even venerate. Though they may not be happy to be featured here, they are side players, this is an adventure in ideas, told through story, not celebrity.

The man sitting before me was Peadar Ó Riada, a titan of Irish culture, and I was after annoying him.

Five months earlier, we had just finished a men’s retreat in Donegal when I received an email from the committee tasked with sending invites to 49 different people in Ireland who had represented the Irish language and culture with distinction. Our contribution was to be honoured at a festival called Feile na Laoch, the Festival of Heroes, that takes place once every seven years, in Cúl Aodh. I was invited as one of the seven ‘Laochra Spóirt’.

I was aware of the magnitude of the festival, though it may only have appeared as an aside on the Irish festival scene. This was as much live ritual as it was a festival and the honour of the invite, particularly as someone on the fringes of traditional Irish culture, was not lost on me. My response wasn’t so much a yes as it was a lengthy and poetic affirmation of my commitment to the tradition the festival upholds.

I told Siobhán and I invited my parents. And I orientated myself towards Macroom, Co. Cork.

In 2018, at the last festival, Seán Óg Ó hAilpín was the standout Laoch, and though I heard it from no one, I was sure he came down from a Múscraí mountainside like a modern day Cúchulainn. Michael D was there. Phil Coulter, Christy Moore, Glen Hansard, Dairíne Ní Chinnéide, Jeremy Irons and Micheál O Muircheartaigh were there.

As an aspiring Irishman, this was big stuff.

The main event runs overnight, from sunset to sunrise, the seven disciplines of Irish creativity are acknowledged over seven hours. There is the parade. The Opening Ritual. And then an hour for each discipline, seven practitioners in each discipline with seven minutes to share their gift with the crowd. People are in for the night. The stage starts facing West and rotates through the night, along with the crowd, finishing facing east, to sunrise. There are the musicians, the storytellers, the poets, the actors, the singers, the dancers and the Laochra Spóirt.

It is an ode to the richness of our culture and the strength of our tradition. It is both local and national and it is truly unique. It is held by the community, but primarily by the O’Riada clan in honour of their great patriarch Seán Ó Riada, whose contribution to the area, to the community and to Irish society is significant enough that a festival every seven years is not out of the ordinary for the man. The scale of his contribution is overwhelming.

The night unfolds in Cúl Aodh, in the ‘Field of Legends’ and it is stewarded by the people of the area. It is an area that feels very sure of itself, in a time where much of community life has succumbed to individualism, it seems that with language, culture and tradition as backbone and sprioc, they are a resilient and self assured people.

So that’s the context. And I didn’t intend to go in to that kind of detail, but it’s better that it’s known. Because this is the scale of the problem that I have just created for myself in sitting with Peadar.

Three magnificent things happened to me that night. I am not writing about them because they are magnificent things that happened to me, I am writing about them because they involve many of us.

In the primary school they had set up a green room, a place where the Laochra and volunteers could go over the course of the night and rest, take soup, drink tea and connect.

I was with two great friends, a couple I had tied the knot for in the previous year, and as night was well into considering the dawn, Siobhan and the kids were tucked up in Coolcower house in neighbouring Macroom. The semi committed were wavering and the man I was with was undergoing something. I could feel his tension in my body and I suggested we go to the green room for soup. Homemade soup from a Cúl Aodh kitchen would set us right. It did.

My friends left and I stayed on chatting to a woman that knew Siobhán and she ended up introducing me to Stephen Rea. Yea, ‘Ned fucking Broy’. I was aware of Stephen Rea and some of his story, I’d watched him on Tommy Tiernan and I was so sure of him that I wasn’t sure of me. There was another man with him that I didn’t know but he was knee deep in The Gate and the Abbey and the characters and the problems and he was cock-sure of how better it all was back in the day. Stephen was in the habit of being human.

Then someone at the table suggested it was a travesty that he didn’t get the Oscar for the Crying Game and I perked up. It’s an interesting thing, the thing that breaks us out of the habit of being human. He’s just been served a dinger and surely he’s heard that same line so often that he isn’t going to bite. This giant of the screen, of the stage, of the Arts, and of Derry and it’s sense of itself. Surely this will drag him out of the dirge his friend has dragged us all in to.

‘Well the Oscars aren’t necessarily selected by people whose opinion you’d respect’ was the first line I heard. My heart sank. That was quickly followed by Stephen pointing out that it’s a bit of a merry go round over there in L.A. and it was Pacino or De Niro or whoever won the thing’s turn to get it that year.

The dissonance of the moment intensified. I had to decide what to do, but I was in no rush because no one seemed to particularly care whether I was there or not. But I did. And this is Stephen Rea. And I’m disappointed.

So in such situations, when I’m alert, my mind goes into the positive version of the much derided ‘fight or flight’ reflex. It’s too painful to stay in silence nodding like I give a continental who won the Oscar. I’m in front of an icon of Irish culture and he’s talking like he’s not over the snub. Now one must be aware reading this, that I am perfectly cognisant of the hierarchy at this table. I am a hurler. No one there cares nor has heard of me and nobody is asking me any questions. And this is Stephen Rea. The most glaring problem to me is that they aren’t playing their role. Their true eldership forgotten, they are in mediocrity, and I can feel it.

So it’s simple. I either excuse myself without fuss to join my two beautiful friends, or I accept that there is a genius in the world and that I am there for a reason, that I have a role to play and that it may even be a role that Ned fucking Broy wants me to play. I don’t want to play it because the odds are stacked against me, but I remember that I am committed to living a life that trusts in the magic of the world and so I orientate myself toward the great man, I change my tone, I ignore completely the man who won’t stop speaking and I hone in on Stephen.

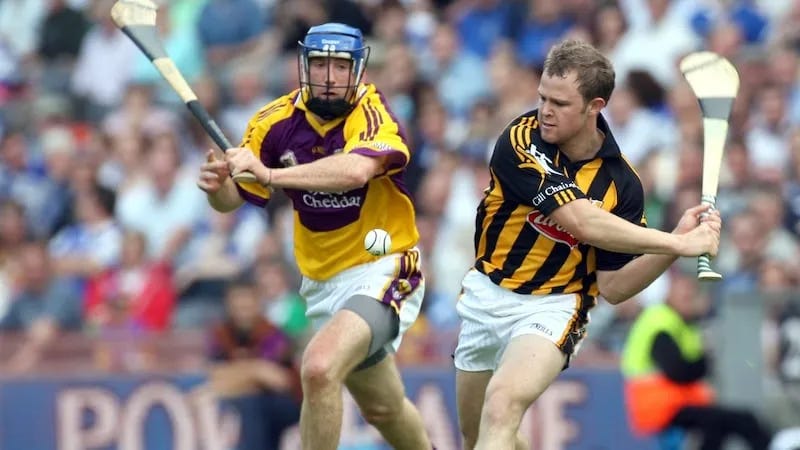

I say to him, looking him squarely in the eyes, his dark curls falling over his beautiful, sad face, that I am a hurler, and that I played for Wexford. I did not say this to curry favour or establish myself, the ‘played for Wexford’ part usually derails that plan. I say ‘Stephen Rea, if I was to reduce the entirety of my hurling experience, the bond with my parents, with my 3 brothers, the people that coached me and the friends that I made, the games that we lost and the games that we won, the briefest of moments when I touched grace, the relationships and the heartbreak and the love for the game, if I was to reduce all of that down to whether or not I won an All-Ireland medal or not, well, I feel these past fifteen years since I finished playing would be time wasted. No. I will not bow down to that way of thinking, and it disappoints me to think that you, a man with such a stellar contribution to Irish life, might do such a thing, even if the scales are different’. I’m paraphrasing, but that was the honest gist of it.

I braced myself.

Stephen Rea appeared relieved that the habit had been broken. We came in to presence together and everyone else in the room faded away. We were locked in and we joined each other in a shared admiration for this cultural renaissance that’s taking place and we revelled in each others commitment to it, this time the scales tipped in my favour, as the younger man still dreaming, and he, the man who’s seen and done it all, glad there’s someone out there still idealistic enough to believe it. He was an elder again, and I drank from the Well in gratitude. The man beside him shrivelled. We went back and forth for a while in mutual respect and good humour and confident my work was done and that my choice was noble, I excused myself and left to find my friends.

Back out in the cold of the night, I relived the moment over a hot flask of tea with Patrick and Sinead and we marvelled at the man who took the stand. Half-an-hour-younger me had earned present-me’s respect. He doesn’t always do so well.

So we continued on our merry way, I found some other people I knew, An Ghaeilge the common story out on the field. I got a hold of Doireann Ni Ghlacáin for a hot second. Ben Mac Caoilte, having delighted to crowd a little earlier, was jamming. An Maonlaoich, just in that morning from an overnight flight from Japan, a man who lives and breathes the significance of the gathering, was in delightful form and the night was taking shape nicely.

But unbeknownst to me, storm clouds were gathering.

So here’s what I had decided in advance of coming. I had been invited. My sense was that one of the reasons I was there was because I had developed a game of hurling that anyone could play. I had made the game accessible. People who had been run out of GAA clubs as youngsters were falling back in love with the great game all over the country. We haven’t really managed to find a way to play a short sided game of hurling in the way Touch Rugby and 5-a-side soccer had. But I had this game at the tips of my fingers.

So I brought 12 hurls in case a game broke out.

Mac Caoilte, the Kilkenny man, was in, naturally. O Maonlaí was in, I having dragged him on to the field earlier in the year at Hidden Hearth festival in Carlow, and subsequently had to drag him off too, such was his genuine love for the game and the experience. There would be 6 Laochra eile, of which Alan Kerrins and Rena Buckley would be 2, so I knew we had the guts of a great game. And word filtered in that what had happened seven years ago was that Sean Óg did indeed come down the hill in style, but that the sporting heroes had just tipped the ball around in front of the stage in an awkward and unbecoming version of the game of hurling. No one knows what to do with hurling outside of a GAA club but this was my bread and butter. So I suggested to the organisers that we play a game at sunrise to finish the experience. No one disagreed.

Game on.

The sun was already up by the time we gathered in the school to make our way down to the Field of Legends, ‘Mise Éire’ our entrance tune, and not for the first time in the night, I was way out on a limb, putting a hurl in Dara O Cinnéide’s willing hand, and persuading the rest of them that this was the way to go. And they trusted me. I was nervous. I had the rest of the players ready on the field below, ready to ‘volunteer’. Plants.

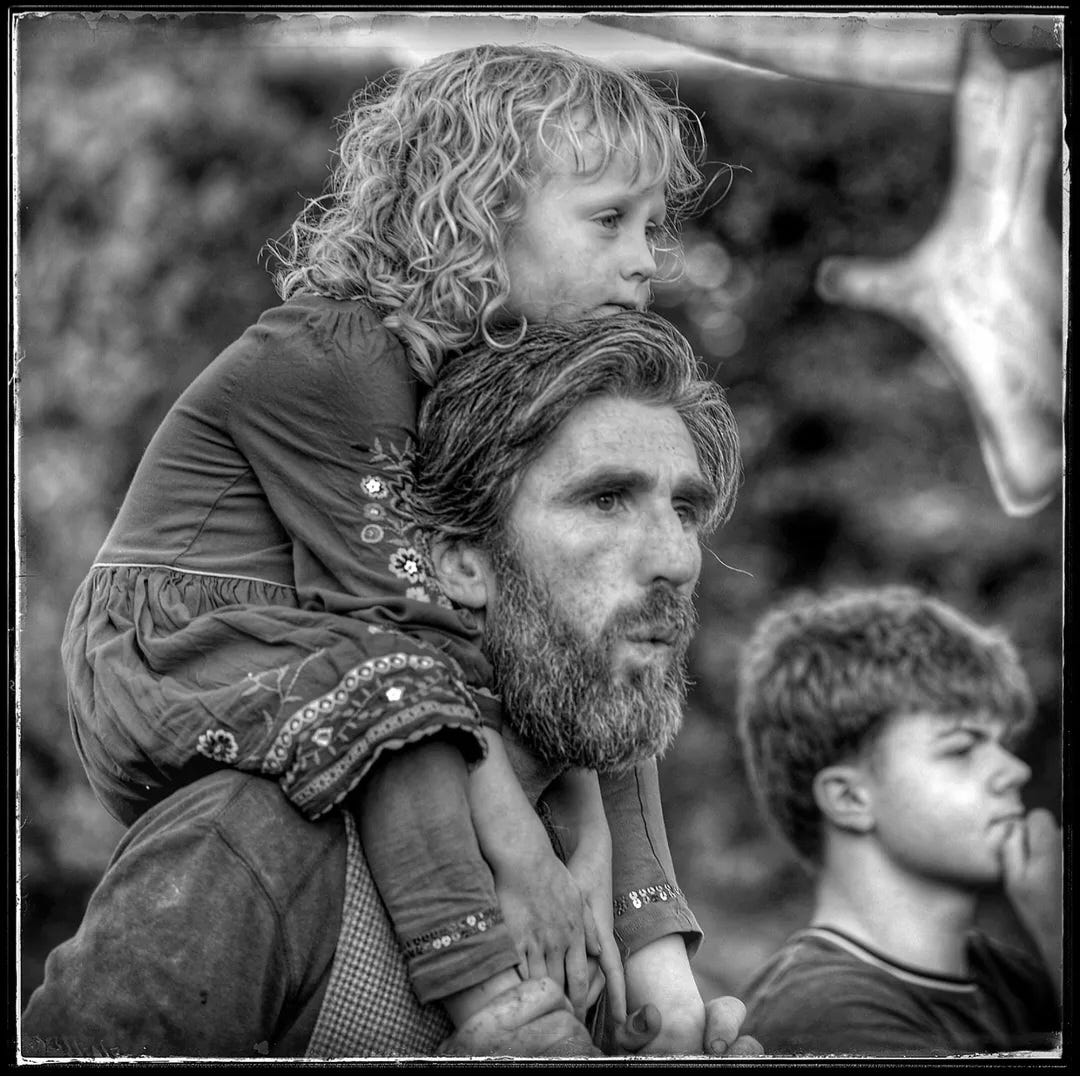

Patrick O Laoighre had hurls out and the makeshift pitch ready, just east of the crowd. It would be the perfect finish. I was bordering on delirious. I had arrived at 7pm for the parade and I marched every step of it with Ériú on my shoulders. I had sat through the full nine hours of festivities. I was committed. I was there in ómós to the the tradition, to the people and the place. My heart was full. I was nervous, but I was pulling through. My mother and father were on the field. The other ‘heroes’ had not long arrived and though they weren’t so sure of me, they could see I was committed. I felt they’d missed a trick in showing up an hour before going on stage. To me it was an initiation, a slow but very real slide in to an altered state where you can earn the respect of Stephen Rea and you can rip up the form book and showcase the game for everyone to enjoy.

We were called to the stage. We accepted the natural crowns, no stranger to me with a wild daughter, and we stood on stage. The energy turned. It was barely perceptible, but I felt it. Our CV’s were laid bare, some faring better than others. Rena Buckley, with 445 All Ireland medals….Diarmuid Lyng….. But there was kindness in the introductions and we stood forward and we waved and then I turned to Peadar and said that we would play a game over to the side and that it was ready to go. I could see O Maonlaí in the crowd chomping at the bit.

Then Peadar told me the game wouldn’t happen because we were behind time and people just wanted to go home.

I was gutted.

I accepted that it was his way and his show and part of me even accepted it because I didn’t know if I could pull it off, if the crowd would get involved or if the whole thing would just peter out and I’d look like a fool in front of my heroes. And some of my heroes were in that field.

I did some interviews, talked to my folks and I went home with my tail between my legs.

But not before myself and Patrick O Laoighre and Sinead Murray and Liam O Maonlaí chanted a proper close to the festival, it had been opened in style but it ended in a way that wasn’t fitting. There was something in the air and it just wasn’t right. Rushed. But in situations like that you circle the wagons with the ones that can and you close it as it should and that’s what we did.

I was committed to staying in the process. There was to be a Pow Wow between all of the feted artists at 2 pm and that was my next focus. The question was, one that I debated intensely with Patrick, would I show up with how I truly felt, or would I shrink under the O’Riada glare. In the conversation it was clear that this was bigger than my little story about it. It represented something greater, the cracks that can sometimes appear when tradition and progress meet.

My feeling was simple. I was there as a devotee of our tradition. People the length and breadth of this country, out of necessity and ignorance, let our culture almost die out, our language was foresaken, our unique footprint and offering to the world was sacrificed at various alters, and some people said no, we won’t do that. These were the people I was dealing with. I love them and I love what they stand for. Where we parted ways was that the tradition had invited me down, I had something to add to it and it was refused. One could easily argue that that we were behind time and that was just the fall of events but there was also an element of ‘yea, come down and drink from the grail, but we don’t want what you’re offering’. We didn’t get to speak. Didn’t get to play. Didn’t get to do anything that resembled the status we were being given and the respect, that up to that point, we were being shown at every turn. And I wasn’t happy with that. Not because I think I’m a big fucking deal. I don’t. But I know in my bones that there was something there to be offered and I knew it was the right call and refusing it, though a fine, fine line, was the very thing people rail against when it comes to tradition. Rigidity. An unwillingness to move through. That’s what it felt like.

Now there are people coming back to the Irish language and her customs in droves, inspired by men like Manchán, a man who made the unconscious and dormant Irish spirit conscious again in so many, and we’re mining ourselves in ways native to us. You mine gold in Africa and oil in the middle east and you mine soul, or the spirit of all things, the Silver Branch, in Ireland. That is our offering to the world and I’ll struggle be told otherwise.

And the language is being butchered to some degree in that process. The ones that use the words for catchy, but always branded life lessons on Instagram don’t know about what the likes of the O’ Riada protected. They don’t know and to muintir Cúl Aodh it may seem like they don’t care. But we must care. If we are to be serious about the language we must kneel at that alter too, even if there’s rigidity. We must pay homage to those who had the tuiscint to understand the value of protecting it and the misneach to see it through.

But those returning to our culture have different experiences, different influences and different ways of being in the world and they have a lot to offer the tradition. My frustration is that we are headed to the same place but staying in separate cars for the journey.

This is what myself and Patrick spoke about. Now this is well in to a chapter of a book so I’ll move towards brevity, but fast forward to 14.00 and I’m sitting with the 25 Laochra left in the village, that were honoured the night before and we are about to have a good old fashioned pow wow. Peadar moderates. The room is empty, with the exception of some of the finest creatives it the country. Playwrites, musicians, poets.

The question is as simple as it is profound. How are we? What’s happening on the ground and what’s the best thing for all of us to speak about given this incredible opportunity? I’m conscious I’m the only Laoch there who isn’t an artist.

The conversations opens with a criticism of the Arts Council and it’s funding methods. It turns out about 8 of the group, mostly men in their 50’s and 60’s, are very invested in this particular topic.

An hour and half later I’m back with Stephen Rea in the green room, the same canyon opening up inside of me. Which way should one go?

Every time the conversation is added to, my heart breaks a little further. I can’t believe that this is what we’re doing. ‘Squabbling for the scraps from Longshanks table’ is the Braveheart line that’s making sense of the situation for me. With the exception of the genial John Spillane, it’s intolerable to the idealist in me. A gentle goodbye to return to the kids would be the easy way out. I’m convinced I can hear An Maonlaoich outside singing his heart out. He assured me after he wasn’t. But someone was singing a song for Ireland tomorrow and every note was going through me, it felt at times as though it was playing me, I was physically wincing at the terrible beauty of the contrast.

All of what was being said was fine. This is work. Man and his bread. It’s serious stuff and these are serious people. Their points and their concerns and their frustrations were all very reasonable but I wasn’t hearing the words and the points. I was hearing the energy behind them. And it sounded to me like a moan. The same way as what I was hearing outside wasn’t just a song. It was Joyful. And it was hopeful.

My legs were shaking but I put my hand up and Peadar acknowledged me and I introduced myself. I introduced myself as a man out of his depth given the company I was in, and that was leading me to be very slow to say anything. I also introduced myself as someone who had underwent the festival. I turned to the great Peadar O Riada and I looked him in the eyes and I told him that I was there to kneel at the alter of the tradition that he and his people had been so courageous to protect.

From there it turned. The room at this point diverged, some came with me to one side of the canyon, primarily the vocal eight, plus Peadar, were firmly on the other. But I didn’t care who was with me. because it didn’t matter, I felt I was following the spirit of things. So I told them all that I was disappointed and I may have even said disgusted, that in a room of the brightest creative Gaels in the country that we were dedicating all of our time to the problem of funding, which, as I understand it, is handed out in any case by those you’re sworn, in some unwritten creed of artistry, to take down.

Out there, I said, O Maonlaí in my mind, is a revolution. A revolution of the Irish spirit that is embracing our language and our customs in ways not seen for a long time, and here we are, the people most ideally positioned to augment the rallying call, many of them elders, talking about the government. I was warned, but I kept going, and I shouldn’t have kept going, but I did. And I kept going not because I had any more to say, I had said everything that I needed to say, but I kept going because it wasn’t my words I wanted them to hear, it was the energy behind them that I wanted them to feel.

I spoke up again a few minutes later when an eminent playwright announced that it was his job to illuminate people with his work. Back to the pulpit.

This time I wanted my words to be heard. I rudely interjected, which I regretted, but I had heard enough. Surely, I suggested, your job is to create the conditions within which the people who pay money to see your work, undergo an illumination for themselves. A fine and grand canyon was opening up between us. I didn’t care. It was arrogant of me, I regret that, but less arrogant by a virtuous mile.

And then it was over. I got to tell John Spillane that we play his music on our Men’s retreats and his song ‘Hey Dreamer’ is a breakthrough point for many of the men.

‘You forgot who you are, you forgot what you are

You forgot what you’re for, you’ve forgotten

You forgot where you’re from, you forgot where you’re goin’

You forgot everything, you’ve forgotten……’

I received some acknowledgement of my own from those that remained silent, their spirit recognising mine, and I knew my work was done. Despite the cost.

And now I was sitting in front of Peadar and I had one more crack. Not crack as critique, but a crack at the truth of things. I was just speaking as I felt because I felt I was in a place where that was welcome. That’s surely us, the shared story we are seeking beneath the divisive mind, a people and a culture able for it’s own immensity.

I apologised, because I was invited as a hero and if I was to have played my role properly I’d have walked down off the stage where he told me not to, and I’ve started that game of hurling whether he liked it or not, because that’s what a proper hero would do. A hero does what needs to be done. That’s what makes him a hero.

He said that the hero fights on the battlefield and is rewarded in the village, he doesn’t fight in the village. It was a fine response.

Talking about hurlers as battle hardened heroes gets my fucking goat though, because it’s hyperbolic in the extreme. Read McSwiney’s Principles of Freedom or Dan Breen’s Fight for Irish Freedom, Emmett from the Dock, listen to ‘Grace’ as biopic, or read about the men who marched to the The Three Bullet Gate in New Ross in 1798, men and women who died for their principles, and then consider the bullshit that’s peddled, often by marketeers, about lads who play a sport. Even though I know Peadar of all people needed no lecture on our history and is well aware of this fact, I wasn’t buying it.

Anyway, I got the sense he was tired of me, or maybe just tired, great man Peadar O Riada, a gorgeous family and a gorgeous community and despite how it all might sound here, it was a win, a big win, for me and for everyone there, it was meaningful and purposeful and beautiful and the honour of the whole thing hasn’t left me.

And I knew Peadar, and Ruth and the rest of the family had brought us in to the dreamtime from which Ireland comes, because an hour later I was back out a Coolcower House, to meet my young family, and who’s coming out the door of the house only Tuireann, newly walking, a year and five months old. He doesn’t react to me, there’s no big playful moment, like we’d normally share, no, he’s in the dreaming too and he keeps me in it, he puts out his hand as he walks by me, knowing that I’ll fall in to step with him, and I do, sure how couldn’t I. And we’re slowly led down eight white garden steps. They’re steep, but he does well, and we get to the bottom and we go across the manicured garden to a bramble branch bursting with blackberries and silently he takes 3 off and he puts one in his mouth but it’s clear that this isn’t final destination. He guides me further down the garden to a gate, finishes the blackberries to free up his purple stained, pudgy little hand and he pulls the gate toward himself. I give him the help he needs, keen to protect his integrity, and we move through. He turns and makes sure the gate is closed. We turn around now and we’re at the waters edge. The mighty Blackwater is in front of us. Tuireann is barefoot. He steps in to the water. I keep his hand but stay on the dry sod. He doesn’t care. We both look south. There is a heron in the middle of the river perched on a branch and now I’m sure we’re in the dreaming. We looked north, toward the bridge, back to society. He looks down at his feet. I look at his feet too. And then he turns, no pressure, no pulling, no sound. He just turns, walks back to the gate, him guiding me or maybe the rhythm of all things guiding us both, he opens the gate with the same intention he had before, and makes sure it closes after him. We walk a few steps to the blackberry bush and this time we both feast on the bounty. From there we head over to the steps and slowly make our way to the top. I know in ways that I’ve never known, that I am in Paradise, being guided by a cherub to the tree of plenty and his banner over us is love. I know that it is in the frightful ordinariness of the moment that it is extra ordinary. Where ordinariness wasn’t enough, it had to become extra ordinary to feel it.

Muintir Cúl Aodh, practicing and protecting the extra ordinariness of life.

We went in to the old house, and that’s all I want to say about that.

Thank you for coming this far with me.

Diarmuid.

This is part of a three part series of writings on the subject of the renaissance in Irish language and custom that we’re currently undergoing and how we may bring unconscious patterns to the surface in order to strengthen the ties that bind us on that journey. You are welcome to follow me, share this piece or to leave a comment below as we travel.

Even though laptop work was pulling me, your words held me right to the very end. Míle buíochas

Jesus Christ that was a wonderful read. Raw and honest and poetic. Maith thú Diarmuid. Thanks for sharing. Your heart rings through it. Your Gaelic soul. Go raibh Maith agat.